The reason why it is important, now more than ever, to discuss the portrayal of alternative sexualities and gender expressions in K-Pop is that Hallyu is no longer a niche. With BTS being invited to the White House to speak on hate crimes perpetrated against Asian Americans, BLACKPINK being appointed as Advocates for the United Nations Conference on Climate Change, and so on and so forth, K-Pop is arguably the most influential cultural power in the world at the moment.With its long-standing legacy and magnanimous fanbase, K-Pop holds immense power as a platform for change. However, the industry doesn’t quite stand up to this potential, at least not on a large scale. In this regard, this article aims to discuss three key concepts that define K-Pop’s contribution to queer discourse: soft masculinity, queerbaiting & the performative representation of homoeroticism/homosexuality through cross-dressing in K-Pop.

Soft Masculinity

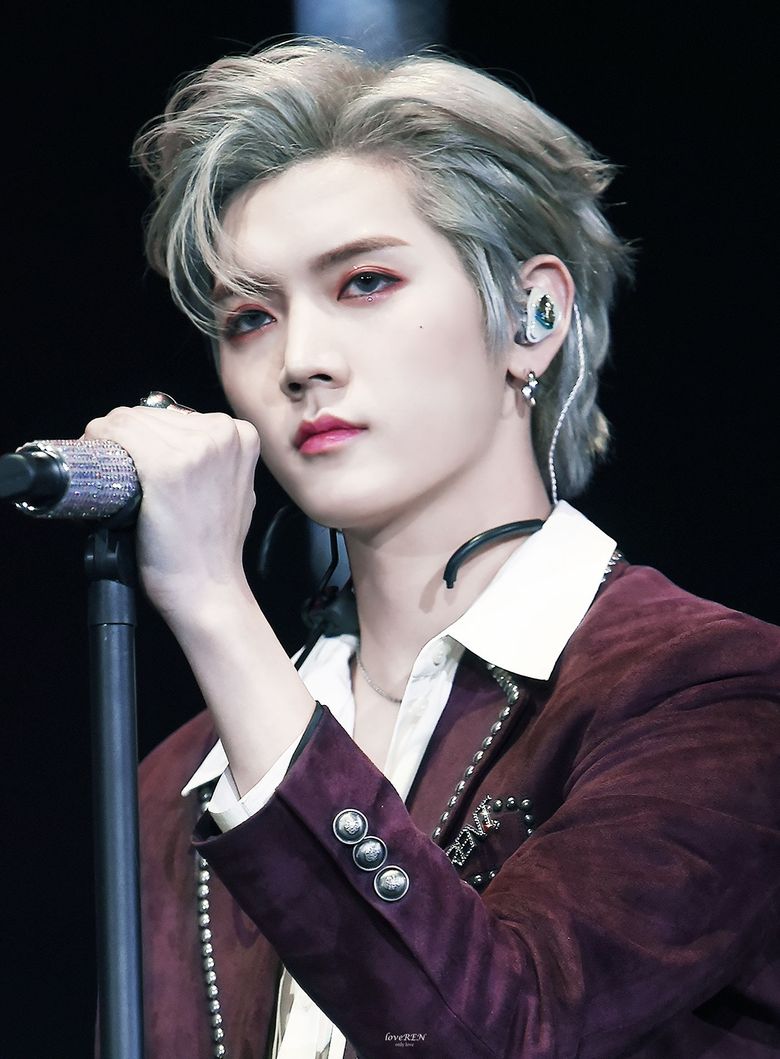

One of the major aspects of K-Pop that has effectively been transformed into a site of debate on gender politics is its redefinition of masculinity. American philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler describes gender as performative, an act of sorts, forced upon individuals by a heteronormative society. However, rather than masculinity being an expression or an effect of socio-biology with the male body producing masculinity, the physical body should be understood as being a neutral landscape on which social determination creates an identity, influenced by the cultural interpretation of gender. As the cultural interpretation of gender can never be static, masculinity can never be solidly defined as one single unchanging concept. However, mass culture has a fixed idea of what ‘true masculinity’ is and it reinforces the same on its consumers and participants.It is for this reason that Western media evaluates K-Pop masculinity in relation to the concept of hegemonic masculinity, constructing a significant difference between the two and thus reproducing cultural distance and furthering the stigma surrounding the consumption of popular culture of the racial Other. The veiled misogyny, harassment, hate speech, and malice that are directed at these young artists on a daily basis simply because they appear to blur the boundaries of gender is appalling. The brunt of this force tends to fall on boy groups that opt for elastic masculinity rather than following Western standards of what the “being” of a man is supposed to entail. However, the Western idea of masculinity is largely outdated and completely fictional.Masculinity, as it is presented in K-Pop, is now a model of masculinity that is a liberating force of change and representation for individuals all across the world who have found a platform for genuine self-expression and creativity in a stifling environment through the normalization of free masculinity. This new and influential breed of masculinity is what Dr. Sun Jung calls ‘pan-East Asian soft masculinity’, best understood by the term ‘kkotminam’ (flower-like men). According to Dr. Jung, “soft masculinity is a hybrid product constructed through the transcultural amalgamation of South Korea’s traditional seonbi masculinity (which is heavily influenced by Chinese Confucian wen masculinity), Japan’s bishõnen (pretty boy) masculinity, and global metrosexual masculinity.“Today, soft masculinity can be deconstructed and reconstructed as per an individual’s own identity and personal sense of masculinity. It is anything that exists in opposition to hegemonic masculinity and is rooted in one’s own truth rather than the performativity of gender ideals. Soft masculinity is not limited to K-Pop idols with angelic visuals but instead, extends to any individual that expresses their gender and sexuality on their own terms.Masculinity is not and cannot be restricted to people who identify as male either. It is equally accessible to female-presenting and non-binary individuals. Soft masculinity is freedom and this freedom was single-handedly brought to us by K-Pop (especially groups like TVXQ, SHINee, EXO, and most notably BTS alongside soloists like Seo TaiJi, Rain, and Jo Kwon), despite it not necessarily being the primary aim of the industry.Soft masculinity was born out of a neoliberal and commercial need to fill a gap that arose from several socio-political circumstances in South Korea whereby masculinity was unshackled from traditional notions of what made a “real” man but its hybridization was carried out through a reiteration of a heteronormative agenda nonetheless. Similarly, the K-Pop industry’s adoption of gender fluidity (not the individual artists’ stance on the same) will perhaps only last as long as it sells. It gives us the illusion of progress, all the while keeping us under control in a capitalist hegemonic system. As such, K-Pop does not radically dispute patriarchy in the slightest but it certainly and inadvertently opens up the scope for its consumers to do so in their own daily lives.

Queerbaiting

“Queerbaiting” refers to the act of courting viewers interested in queer narratives with ambiguous implications to the same without ever clearly confirming or denying the non-heterosexuality of the characters involved. Born out of fandom and “shipping” culture in the 2000s, it is, at its core, a marketing ploy to mislead this portion of the audience by hinting at a possible queer relationship while retaining the mainstream consumer base by avoiding any definitive indication of it. Not only is this damaging to the LGBTQIA+ community because of its inherently exploitative model but also, it does nothing to raise awareness about real issues. However, whether a media text is guilty of queerbaiting or not, depends from person to person as the definition can effectively change in accordance with cultural contexts. For instance, when Red Velvet’s subunit IRENE & SEULGI released the music video of the song ‘Monster’, featuring a visibly sapphic on-screen relationship, some viewers opined that it was a clear case of queerbaiting and fetishization of WLW relationships whereas others asserted that it contributes to the normalization of queer characters in K-Pop. Neither can be claimed as the right or wrong answer because one cannot speak for all queer individuals and their personal experiences with the content. While it is true that a narrative does not have to spell it out for us whenever there’s a queer relationship involved, it is equally fair to demand that homosexual relationships not be used as an aesthetic or gimmick for promotion. In another example of a sapphic relationship portrayed in a K-Pop music video, we have MAMAMOO’s MoonByul and SEORI’s ‘Shutdown’. Unlike ‘Monster’, the lyrics of ‘Shutdown’ clearly express a romantic relationship between two women, and the music video does absolute justice to the same. This is undeniably the most respectful and brilliant representation of a WLW relationship in K-Pop, leaving no room for speculation otherwise. On the other hand, we have ’libidO’ by OnlyOneOf, which was subject to much controversy because of its “suggestive” choreography. However, when we look at the music video for the song, it plays out like a BL coming-of-age drama and there are simply no two ways about it. OnlyOneOf are not shying away from the straightforward portrayal of a gay relationship and yet, they are receiving backlash for the same, which speaks volumes of the concerned audience, not their art.When it comes to queerbaiting outside of fiction, the lines are once again dangerously blurred. When a K-Pop idol expresses his affection for another idol, usually a member of their own group, in a physical manner (“skinship”), many fans and non-fans alike can be quick to dub that action as queerbaiting or fanservice. However, it is important to remember that we stand in no place to dictate or predict whether another individual’s expression of love is driven by romantic attraction or platonic feelings. It can only be up for criticism if it is deliberately “performed” for profit rather than coming from a place of support towards the queer community, as instructed by either their companies (“queerbaiting”) or demanded by fans themselves (“fanservice”), feeding further into the commoditization of idols. Even and especially then, artists deserve none of the flak for it (mostly because they have no say in how they’re presented), and more importantly, absolutely no one is entitled to the knowledge of their sexualities or preferences.It is also interesting to note here that the South Korean society and the majority of its K-Pop audience, largely adores LGBT relationships when it comes in the form of fanservice. However, real queer relationships and individuals are still frowned upon. The recent homophobic attack on HOLLAND, an openly gay K-Pop idol, is regrettably an outcome of this mentality.

Cross-dressing in K-Pop

With the unprecedented global success of K-Pop, it has been rather imperative for the K-Pop industry to keep up with the times and represent homosexuality in a politically correct way. However, that has not always been the case. To elaborate, we will be focusing on male cross-dressing performances that have been staples of Korean entertainment over the years.Drag and cross-dressing in Korea date back to the ancient art of talnori. Tal means mask and nori refers to a wide range of Korean performing arts. In K-Pop, not only does this allow for a presentation of queer identities that challenge heterosexist norms through the mask of cross-gendering but in true theatrical fashion, an audience is able to distinguish the actor (in this case, the male K-Pop idol), from the female character he plays, thus transforming the stage into an alternative space. However, because this performance is not read as queer, it also reinforces compulsory heterosexuality. As Dr. Sun Jung puts it in “K-Pop beyond Asia: Performing Trans-Nationality, Trans-Sexuality, and Trans-Textuality”, these hyperbolic campy feminine performances are well received because “they are pretty but not actually gay”. One example of such a cross-gendered play was a performance of Girl’s Day’s song ‘Something’ by TVXQ’s ChangMin, SUPER JUNIOR’s KyuHyun, SHINee’s MinHo, and EXO’s SuHo. The perceived aim of the performance was not for the men to pass as women but rather to highlight how these men fail in their efforts to act as women and it is this discrepancy that is the primary source of humour and entertainment. At the same time, the idea that these men are putting on a show is made glaringly obvious through deliberate attempts at breaking the fourth wall. However, if the men dressed as women get too good at it and their performance is too convincing, it starts to teeter on the lines of homoeroticism, which is immediately rejected. As a result, while such performances have the potential to subvert the heteronormative order, they do not directly challenge the status quo. Homosexuality is thus either penalized or fetishized, with no in-between. On the brighter side, deliberately homoerotic performances in K-Pop, although rare, are not always offensive. An example of the same would be INFINITE’s Lee SungYeol and Lee SungJong’s performance of ‘Troublemaker’ by TROUBLEMAKER. Gender is fluidized, allowing a man to represent femininity without the overt imitation of women. SungYeol never attempts to “play” a woman even though he is dressed as one. Neither does he try to evoke laughter by exhibiting discomfort. He simply performs with diligence, and it shows.In conclusion, queer representation through cross-dressing, although at times problematic, has normalized the performance nonetheless, and drag has finally found an opening for free expression in South Korea despite having been reduced to a forbidden art for so long. Every dark cloud has a silver lining after all! What are your thoughts on the representation of queer identities in K-Pop? Tell us in the comments section down below! Netizens Discuss K-Pop Generations: What Generation Of K-Pop Are We In? FANBUZZ|Apr 6, 2022 Netizens Discuss The Importance Of Domestic Vs. International Fan Bases: Is One More Significant Than The Other? FANBUZZ|Mar 30, 2022